A new hotdog stand sprang into existence with the subtlety of a redneck at midnight on the fourth of July.

This was Frank’s Franks!

And at its helm was Frank — a man as eccentric as he was eloquent.

With a voice that could sell sun-tanning oil to a vampire, Frank promised to transform the humble hotdog into a beacon of culinary delight and community spirit. His vision was nothing short of revolutionary. His goals loftier than a kite in a hurricane.

Frank was, without a doubt, the Sultan of sausages.

Frank’s Franks burst onto the scene with an audacious strategy:

Free hotdogs for everybody!

The news spread faster than a cat with tail on fire. All it took was just one scrumptious bite of those delicious dogs, and customers were hooked.

They told their friends — statistically, around 11 each — who then told their friends, who then told their friends, and so on.

Soon, Frank’s Franks was the hottest spot in town, teeming with people who couldn’t get enough of the free, mouth-watering hotdogs and the infectious buzz of the crowd.

The city was enchanted.

Who wouldn’t be?

Amazing hotdogs, free food — and all their friends were there too! Frank, with his eloquent speeches and promises of greatness, became a local legend.

But amid the euphoria, no one paused to ask a critical question:

“How was Frank making any money?”

Before long, billboards began sprouting around the hotdog stand like mushrooms after a rainstorm, advertising everything from local boutiques to the latest tech gadgets.

At first, it was a minor inconvenience — a small price to pay for such an incredible experience.

But Frank, ever the opportunist, secretly looked upon inconvenience as a form of fiscal expedience. As in, to profit better, he made the experience worse.

And gradually, every so slowly, he began selling more and more advertising space. The once charming hotdog stand transformed into a labyrinth of ads.

The parking lot became a canvas of corporate logos, bun wrappers were plastered with promotions, and even the hotdog buns bore cryptic symbols that resembled ancient hieroglyphics — if ancient hieroglyphics had been designed by a particularly aggressive marketing team.

Soon, patrons found themselves consuming their hotdogs in booths covered in ads. To make matters worse, between each hotdog, a jolly eccentric mascot would appear, belting obnoxious jingles and urging them to stay for another.

They’d even ask for a tip!

And yet, the promise of unlimited free hotdogs still held its allure.

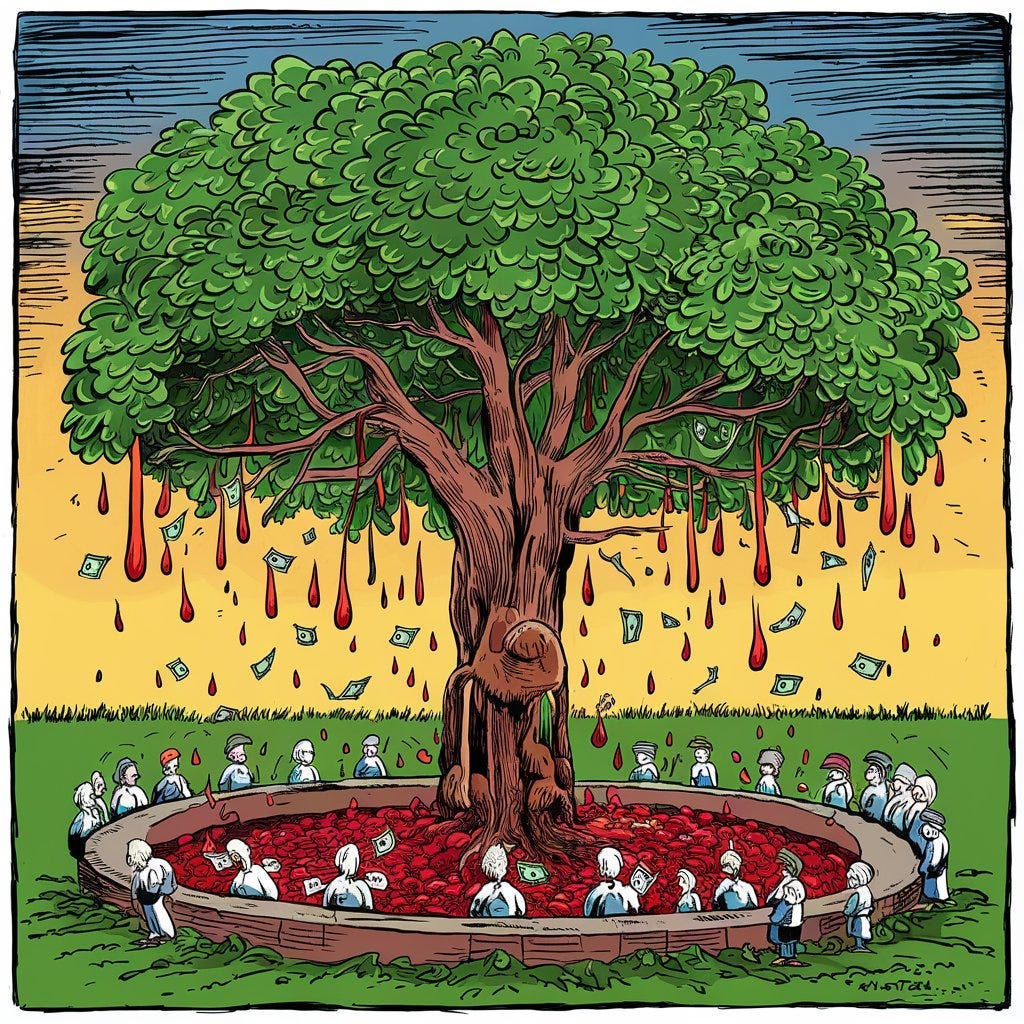

Curiously, no one really knew where the hotdogs were made or how they could be so cheap.

Whispers of dark origins circulated — rumors of child labor, deadly working conditions, and hotdog supervisors who used the word “synergy” far too often. A suspicious number of stray dogs called the factory home.

As a result of these rumors, some customers started calling the end product ‘blooddogs’ — but the attraction of free food was too strong to heed these grim tales.

Then there was the talk of Frank’s draconian work rules.

Timed bathroom breaks ran with the efficiency of a drill sergeant and the empathy of a rock in a slingshot. Employees had to sprint to the restroom and back, with a stopwatch that made Olympic timekeepers jealous.

One second late?

Suddenly, their labor was as free as the hotdogs.

And unions?

Frank quashed them faster than you could understand a Scotsman pronounce ‘collective bargaining’ — so, expedient, but not instantaneous.

As the city gorged itself on Frank’s Franks, other restaurateurs saw the success and wanted in on the action. They knew they had to follow in Frank’s footsteps, and did so.

The problem?

A generation of townspeople was already hooked on hotdogs. Some adventurous souls occasionally jumped ship, savoring a burger or a taco before inevitably returning to Frank’s Franks time and time again.

Oddly, the younger folks seemed to prefer tacos over Frank’s offerings, and they took to calling Frank and his loyal patrons ‘Boomdogs,’ a term blending generational derision with culinary contempt.

In the end, most of these young folks swore off hotdogs completely.

And working in general.

Advertisers, who had initially flocked to the taco and burger stands seeking refuge from Frank’s relentless commercialism, soon found themselves in the same situation.

Ads covered every surface; from napkins to ketchup packets to bathroom stalls.

The entire fast-food ecosystem had turned into a bizarre landscape of relentless marketing and diminishing returns.

One unfortunate customer, who had the misstep of falling asleep after eating no less than 23 weiners — he was on Paleo — even ended up with an ad tattooed on his back!

Fortunately, for his sake, it was for Old Spice.

And everyone loves Old Spice.

Meanwhile, the quality of the hotdogs and everything else at Frank’s Franks steadily declined. Once mouth-watering delights, the hotdogs now tasted like soggy cardboard tubes — yet no one seemed to mind.

The copious legal*** preservatives, combined with a secret recipe of 11 snouts and slices, ensured the flavor stayed vaguely akin to the original taste.

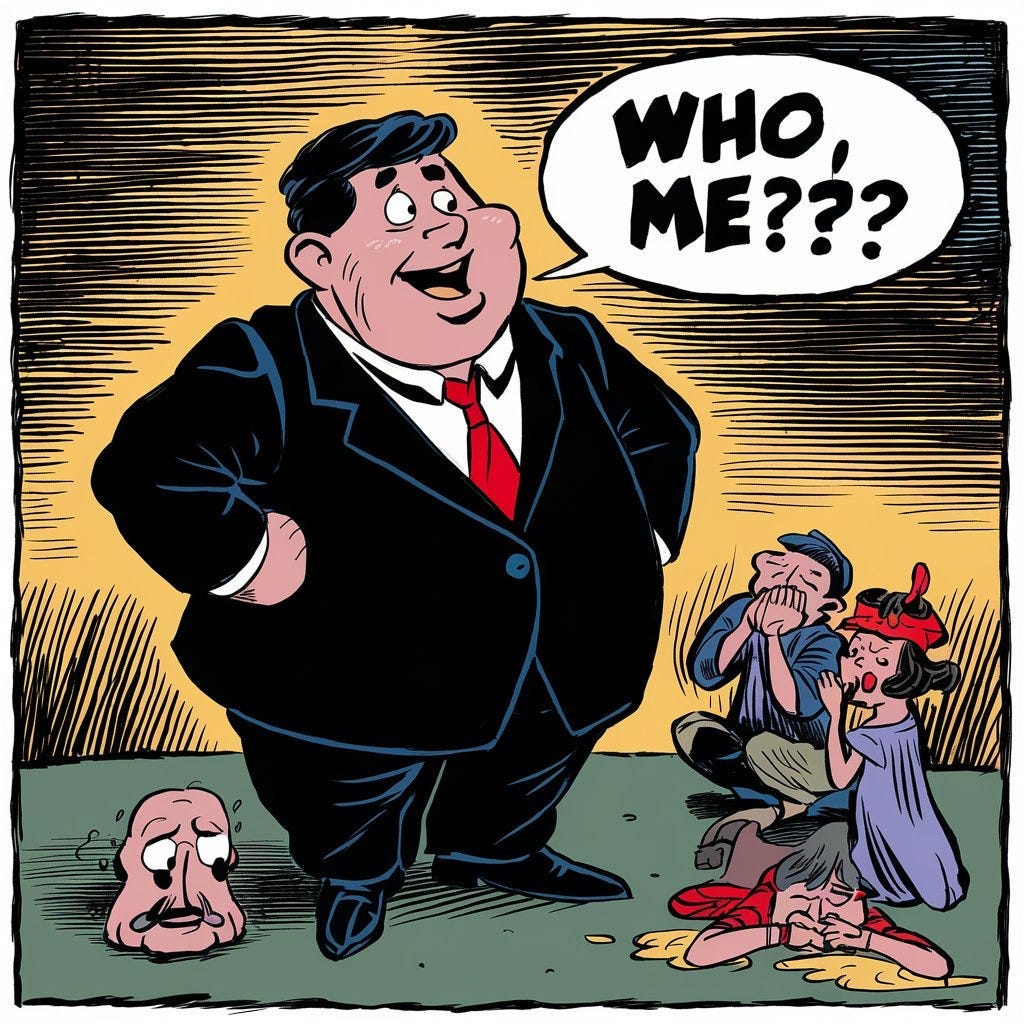

As time went on, Frank — ever the shrewd businessman — quietly bought the taco and burger stands. This move raised a few eyebrows, but Frank was well-prepared.

He paid the politicians to declare it a triumph for the local economy.

“It’s trickle-down economics at its finest!” they proclaimed.

The townspeople nodded along, not having seen an antitrust case in 25 years and quite forgetting what the term even meant.

Frank knew exactly how to push the envelope.

People wanted to leave, but their friends were still there. And besides, they didn’t really like burgers or tacos. Frank’s Franks was still the best option, if only by default.

Advertisers, once enthusiastic about the bustling crowds, now faced exorbitant rates for minimal ad space. Despite the poor returns, they had no choice but to stay — there was nowhere else to go.

The hotdog stand’s pricing was extortionate — but so were the prices at the burger bin and the taco truck.

“Oh well,” thought the marketers. “We have to spend our budget or lose it next year (and possibly our jobs).”

“Oh well,” thought the marketers’ bosses. “Pricey, but I like the way you think. Approved.”

After all, bigger budgets made these bosses look more important, which is exactly why CEOs are CEOs in the first place.

Money flowed in.

The customers lamented the decline in hotdog quality, but stayed because their friends stayed. The advertisers bemoaned the poor returns but stayed because the customers stayed.

From the perspective of Frank, this was called the ‘last mover advantage’ — no one wanted to be the first to leave unless everyone else left, too.

The entire community’s habits and food budgets had warped around these addictive weenies, whose main secret ingredient turned out to be greed (with just a pinch of salt).

The salt, of course, was extracted from the tears of the hotdog factory workers. No wastage allowed.

The townspeople now had an epidemic of type II diabetes, high cholesterol, and a general ever-present sense of angrxiety — a combination of anger and anxiety directed at anyone and everyone but Frank himself.

Frank had played the long con and won.

And so, despite the many negative effects on the town, everything was okay in the end.

Because Frank had not one, but two luxury yachts shaped like giant hotdogs, complete with mustard-yellow sails and relish-green trim!

And really, isn’t that what life is all about?

J.J. Pryor

Addendum

This story was inspired by the terrific writing of Cory Doctorow, who coined the term ‘enshittification’ in 2022.

And as per a not-yet-enshittified Wikipedia, here’s a good definition:

“Enshittification is a pattern where online services and products experience a decline in quality over time.

It is observed as platforms transition through several stages: initially offering high-quality services to attract users, then shifting to favor business customers to increase profitability, and finally focusing on maximizing profits for shareholders at the expense of both users and business customers.

This process results in a significant deterioration of the user experience.

A variety of platforms have been described as examples of this, including Airbnb, Amazon, Facebook, Google Search, Twitter, Netflix, Bandcamp, YouTube, Reddit, Quora, Uber, and Unity.”